Published with Blogger-droid v1.6.5

Monday, November 22, 2010

Friday, October 15, 2010

Sputnik-2 and the Dog in space

Sputnik-2

| |

| Operator | Soviet Union |

|---|---|

| Major contractors | OKB-1 |

| Mission type | Earth Science |

| Satellite of | Earth |

| Orbits | ~2,000 |

| Launch date | November 3, 1957 at 02:30:00 UTC |

| Launch vehicle | R-7/SS-6 ICBM |

| Mission duration | 162 days |

| Orbital decay | April 14, 1958 |

| COSPAR ID | 1957-002A |

| Homepage | NASA NSSDC Master Catalog |

| Mass | 508.3 kg (1,120 lb.) |

| Orbital elements | |

| Semimajor axis | 7,314.2 km (4,545 miles) |

| Eccentricity | .098921 |

| Inclination | 65.33° |

| Apoapsis | 1,660 km (1,031 miles) |

| Periapsis | 212 km (132 miles) |

| Orbital period | 103.7 minutes |

| Instruments | |

|---|---|

| Dog Laika: | Biological data |

| Geiger counters : | Charged particles |

| Spectrophotometers: | Solar radiation (ultraviolet and x-ray emissions) and cosmic rays |

Following the excitement over the first artificial Earth satellite, Premier Khrushchev urged Korolev to launch a second satellite in time to celebrate the 40th anniversary of the Soviet revolution. Object-D was still months away from completion, but some experiments were ready to deploy immediately. PS-2 was assembled in less than a month, but was able to perform the first serious scientific experiments in orbit.

Korolev was interested in manned spaceflight at a very early point, and in 1949 he asked Vladimir Yazdovsky, an army physician, to head the biomedical research effort to study this problem. In 1955, Oleg Gazenko joined Yazdovsky's team and worked closely with him on problems of space biology and medicine. These experiments began with Korolev's R-1A missile, which tested the new concept of an ejectable warhead. Whole rockets, like the German V-2, sometimes broke up from aerodynamic stress as they approached their target, a problem that would get worse with larger and faster missiles. Yazdovsky launched the first dogs, named Dezik and Tsygan, on June 22 1951, using an R-1A sounding rocket and a sealed capsule with oxygen supply and soda-lime scrubbers to remove carbon dioxide. From 1954 to 1956, the R-1D and R-1E rockets carried pairs of dogs wearing pressure suits with plexiglass bubble helmets. The dogs were ejected from the rocket, one at 75-90 km altitude and the other at 35 km, to test different landing systems. From 1957 to 1960, the R-2A and R-5A went dogs to 200 and 480 km. For these experiments, Yazdovsky returned to the use of sealed compartments. In all, 29 launches with pairs of dogs took place Problems of interest included biometric sensors and telemetry, supplying the passenger with oxygen and food, studying the effects of weightlessness, and studying the effects of high acceleration that takes place during launch and reentry. These rockets also contained experiments for measuring primary cosmic rays, the far-ultraviolet spectrum of the Sun, micrometeorites and the composition and ionization of the outer atmosphere. Experiments housed on Sputnik-2 and Sputnik-3 were all tested on geophysical rockets.

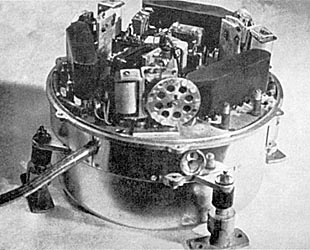

The PS-2 satellite consisted of three units mounted in a conical frame, with a total mass of 508.3 kg. At the top was an experiment to measure solar x-ray and far ultraviolet radiation. Below that was a spherical unit which was essentially the same as the original PS-1. Unlike PS-1, the 20 MHz signal was a more rapid pulsation, and the 40 MHz channel sent a continuous carrier. Below that was a cabin to carry an experimental dog. PS-2 remained attached to the rocket sustainer stage while in orbit. This permitted the R-7 (Tral) telemetry system to transmit science data. While the public was encouraged to listen for the 20 and 40 MHz signals, the scientific data would be sent on classified frequencies, 66 and 70 MHz. The sustainer stage also housed two Geiger counters. The aluminum dog cabin was adapted from a system used to carry dogs on the R-2A sounding rocket. It was 80 cm long and 64 cm in diameter. A ventilator fan at the top would turn on, if the temperature rose above 15° C. On either side of the dog, two large compartments contained plates of potassium superoxide. This chemical reacts with carbon dioxide and water vapor and emits oxygen (note small red circulating fans in the image above). A control system (above the left superoxide compartment) would stop regeneration if the pressure went above 765 mm Hg, to prevent the dog from being poisoned by oxygen. Food and water requirements were simultaneously met by a gelatinous nutrient made from water, agar agar, dried-bread powder, powdered meat and beef tallow. This was delivered by a cartridge belt arrangement that doled out portions for the dog to eat at regular intervals. A 3 liter supply was meant to last seven days, which was also how long oxygen regeneration would last. Urine and feces were collected by a tight fitting rubber cup, and sent to a sanitation reservoir filled with activated charcoal and dried moss.

The sun emits far ultraviolet and x-ray radiation from the high temperature plasma in its corona. Since these wavelengths did not penetrate the atmosphere, American and Soviet scientists had studied them with sounding rockets, but there was no long term study to connect this radiation with changes in the ionosphere. Prof. Sergey Mendalshtam, at the Lebedev Institute of Physics, designed a detector that was ready in time for the PS-2 mission. It consisted of three photomultiplier tubes, aimed at 120° intervals. A filter wheel revolved in steps to select different wavelengths: copper (0.14-0.3 nm), beryllium (0.5-1.0 nm), aluminum (0.8-2.1 nm), polystyrene(4.4-10.0 nm) lithium fluoride and calcium fluoride for the hydrogen Lyman-α wavelength (121.5 nm) and quartz (great than 150 nm). At Moscow State University, cosmic-ray expert Sergey Vernov and his colleagues were preparing a Geiger-counter unit for Object-D. The KS-5 cosmic counter (kosmicheskii schetchik) consisted of an SI-17 gas discharge tube, commonly used in high-altitude balloon studies of cosmic rays. Given a power budget of only 2 watts, they could not use vacuum tube for the electronics. They considered neon-lamp logic and cold-cathode thyratrons, but eventually decided to use the new technology of solid state transistors and diodes. They were surprised by the launch of Sputnik-1, and when Vernov heard about PS-2, he rushed to meet with Korolev. Arguing the importance of cosmic-ray measurements for manned spaceflight, he convinced Korolev to let them install their device on the upcoming mission. They were given enough space on the sustainer stage for two KS-5 units, and a Tral telemetry channel was allocated. But there was no additional electrical power available for them. With only three weeks until launch, the KS-5 was quickly modified to contain its own battery power supply.

The second artificial Earth satellite was launched on November 3, 1957, at 2:30:42 GMT. It reached an orbit with a perigee of 225 km, apogee of 1671 km and a period of 103.75 minutes. The plane of the orbit was inclined 65.33°. A strong spring ejected the conical fairing, and two oxygen gas jets backed the satellite and sustainer stage away, to avoid collision with the fairing. Two symmetrically placed jets were used, instead of one as on Sputnik-1, to avoid imparting extra rotation to the satellite. Once in orbit, the Tral system changed from reporting rocket telemetry to a program of switching between four sets of mission data: solar x-ray data, cosmic-ray counts, biometric data on the experimental dog, and temperature readings from 12 points on the spacecraft. The satellite completed 2570 orbits. It was observed reentering the atmosphere over the West Indies on April 14, 1958.

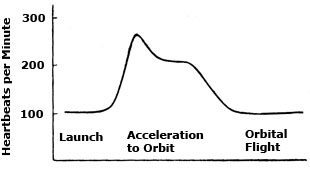

Sputnik-2's passenger was Laika, a small dog of mixed breed (possibly siberian husky and terrier) collected off the streets of Moscow. In preparation for the flight, Laika was trained to sit in the cabin and get used to the noises and acceleration of launch and to the harness and waste-collection apparatus. Four biometric readings were radioed to Earth. Silver EKG electrodes were implanted in the chest to measure the heart rate, and a piezoelectric blood-pressure sleeve was surgically placed around the carotid artery in the neck. These were kept carefully bandaged and cleaned with alcohol to avoid infection where wires emerged through the skin. Respiration rate was measured by strain gauges in a belt around her chest. The dog was chained in place, with limited freedom to lie down or stand, and motion sensors reported activity. Heart-rate telemetry indicated that Laika was stressed by the launch and possibly surprised for a time by the transition to weightlessness. Respiration rate increased, reaching 4 times normal during the period of greatest acceleration, when pressure made it physically difficult to breath. 5-10 minutes after the achievement of orbit, the dog calmed and her readings and activity returned to normal. Yazdovsky was concerned from the start about the problem of heat, both from the Sun and from the dog's body. The decision to keep the satellite attached to the sustainer stage may have exacerbated the problem. During the flight, the cabin became steadily warmer. Sometime after the 4th orbit (5 to 7 hours) the biometric telemetry system failed. Although Laika's exact fate is unknown, ground simulations suggested that she died from overheating soon after the 3rd or 4th orbit. Official news reports described the results from the early hours of the experiment. Subsequently, no details were announced except to suggest that Laika, who had become an instant celebrity, was fine. When the radio transmitter stopped on November 10, officials began to acknowledge that Laika would die. An Italian communist paper reported (and later retracted the story) that Laika was euthanized by poison, but there is no evidence that such a thing was ever planned or implemented in the life support system.

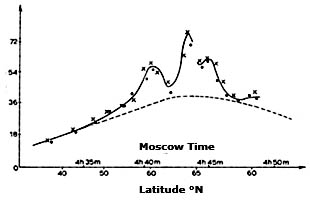

Data from Mandelshtam's solar x-ray experiment was disappointing. While changes could be seen from the filter wheel steps, for the most part the sensitive photomultiplier tubes appeared to be jammed by intense radiation that had no connection with the direction of the Sun. His team did not publish the results, and in retrospect, Mandelshtam realized that they had seen the effects of proximity to the Earth's radiation belt. Vernov's team had better luck with the KS-5, and they received data from November 3rd to the 9th. Of particular interest was an event on November 7, when an elevated level of radiation was seen at about 60° latitude. We know now that this is where the fluctuating outer radiation belt approaches the Earth most closely. They had no way at the time of realizing the significance of this anomaly. The signal from Sputnik-2 could only be received over the territory of the USSR. The apogee of the orbit occurred high over the south pole, where it would have penetrated well into the radiation belt, but that data was never seen. Because the mission data was being sent on a classified channel, Vernov could not ask for help from his international colleagues, and he would be mindful of that problem on the next satellite mission.  In 1957, Laika became the first animal launched into orbit, paving the way forhuman spaceflight. This photograph shows her in a flight harness. Romanian stamp from 1959 with dog Laika |

Wednesday, October 13, 2010

The Space Age Begins

The R-7 (Russian: Р-7) was the world's first true intercontinental ballistic missile, deployed by the Soviet Union during the Cold War from 1959 to 1968. To the West it was known by the NATO reporting name SS-6 Sapwood and within the Soviet Union by the GRAU index 8K71. In modified form, it launched Sputnik, the first artificial satellite, into orbit, and became the basis for the Soyuz space launcher and the Molniya, Vostok and Voskhod variants.

The widely used nickname for the R-7 launcher, "semyorka", simply means "the digit 7" in Russian.

|

| SS-6 rocket. (NASA) |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| R-7 8K72 "Vostok" permanently displayed at the Moscow Trade Fair at Ostankino; the rocket is held in place by its railway carrier, which is mounted on four diagonal beams that constitute the display pedestal. Here the railway carrier has tilted the rocket upright as it would do so into its launch pad structure -- which is missing for this display. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

| Major contractors | OKB-1, Soviet Ministry of Radiotechnical Industry |

|---|---|

| Mission type | Atmospheric studies |

| Satellite of | Earth |

| Orbits | 1,440 |

| Launch date | 19:28:34, October 4, 1957 (UTC) (22:28:34 MSK) |

| Launch vehicle | Sputnik rocket |

| Mission duration | 3 months |

| Orbital decay | 4 January 1958 |

| COSPAR ID | 1957-001B |

| Homepage | NASA NSSDC Master Catalog |

| Mass | 83.6 kg (184.3 lb) |

| Orbital elements | |

| Semimajor axis | 6,955.2 km (4,321.8 mi) |

| Eccentricity | 0.05201 |

| Inclination | 65.1° |

| Apoapsis | 7,310 km (4,540 mi) from centre, 939 km (583 mi) from surface |

| Periapsis | 6,586 km (4,092 mi) from centre, 215 km (134 mi) from surface |

| Orbital period | 96.2 minutes |

Sputnik 1 (Russian: "Спутник-1" Russian pronunciation: [ˈsputʲnʲək], "Satellite-1", ПС-1 (PS-1, i.e. "Простейший Спутник-1", or Elementary Satellite-1)) was the first Earth-orbiting artificial satellite. It was launched into an elliptical low Earth orbit by the Soviet Union on 4 October 1957, and was the first in a series of satellites collectively known as the Sputnik program. The unanticipated announcement of Sputnik 1's success precipitated the Sputnik crisis in theUnited States and ignited the Space Race within the Cold War. The launch ushered in new political, military, technological, and scientific developments. While the Sputnik launch was a single event, it marked the start of the space age.

Apart from its value as a technological first, Sputnik also helped to identify the upper atmospheric layer's density, through measuring the satellite's orbital changes. It also provided data on radio-signal distribution in the ionosphere. Pressurized nitrogen, in the satellite's body, provided the first opportunity formeteoroid detection. If a meteoroid penetrated the satellite's outer hull, it would be detected by the temperature data sent back to Earth.

Sputnik 1 was launched during the International Geophysical Year from Site No.1, at the 5th Tyuratam range, in Kazakh SSR (now at the Baikonur Cosmodrome). The satellite travelled at 29,000 kilometers (18,000 mi) per hour, taking 96.2 minutes to complete an orbit, and emitted radio signals at 20.005 and 40.002 MHz which were monitored by amateur radio operators throughout the world.The signals continued for 22 days until the transmitter batteries ran out on 26 October 1957. Sputnik 1 burned up on 4 January 1958, as it fell from orbit upon reentering Earth's atmosphere, after travelling about 60 million km (37 million miles) and spending 3 months in orbit.

Tuesday, October 12, 2010

Sergey Korolyov

Sergey Pavlovich Korolyov was born on 12 January 1907 in Zhytomyr, a small provincial centre in central Ukraine, then part of Imperial Russia, and died on 14 January 1966 in Moscow. He was the head Soviet rocket engineer and designer during the Space Race between the United States and the Soviet Union in the 1950s and 1960s. Korolyov's pivotal role in the Soviet space programme was kept a closely-guarded secret until after his death. Throughout his period of work on the programme he was known only as the "Chief Designer".

Although trained as an aircraft designer, Korolyov's greatest strengths proved to be in design integration, organisation and strategic planning. A victim of Stalin's 1938 Great Purge, he was confined for almost six years, including some months in a Siberian gulag. Following his release, he became a rocket designer and a key figure in the development of the Soviet ICBM programme. He was then appointed to lead the Soviet space programme, overseeing the early successes of the Sputnik and Vostok projects. By the time he died unexpectedly in 1966, his plans to compete with America to be the first nation to land a man on the Moon had begun to be implemented.

He rise began in 1944, when after years of incarceration along with other Soviet rocket pioneers, he was rehabilitated. In 1945, he was commissioned into the Red Army, with a rank of colonel and, along with other rocket experts, he was flown to Germany to gather information on the German V-2 rocket. The Soviets placed a priority in reproducing lost documentation on the V-2, and studying the various parts and captured manufacturing facilities. In 1946 it was decided by the Soviet government to ship some 5000 German rocket workers back to Russia, effectively kidnapping them, although they were treated relatively decently.

Stalin had decided to make missile development a national priority, and the German "recruits" were placed into a new institute created for the purpose, the NII-88. Development of ballistic missiles was put under the military control of Dimitri Ustinov, with Korolyov serving as chief designer of long-range missiles. Korolyov demonstrated his organisational abilities in this new facility, keeping a dysfunctional and highly-compartmentalised organisation operating.

With the documents reproduced, thanks in part to disassembled V-2 rockets, the team now began producing a working replica of the rocket. This was designated the R-1, and was first tested in October 1947. A total of eleven were launched, with five landing on target. The Russians continued to utilise the expertise of the Germans on their rocket designs until about 1952 when the first groups began to return home; the last group returned in 1954.

In 1947 the NII-88 group under Korolyov began working on more advanced designs, with improvements in range and throw weight. The R-2 doubled the range of the V-2, and was the first design to utilise a separate warhead. This was followed by the R-3, which had a range of 3000 kilometres, and thus could target bases in the UK. However Glushko couldn't get the engines to develop the required thrust, and the project was cancelled in 1952.

That same year work began on the R-5 which had a more modest 1200 km range. This completed a successful first flight by 1953. However, the first true intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) would be the R-7 Semyorka. This was a two-stage rocket with a maximum payload of 5.4 tonnes, sufficient to carry the Soviet's nuclear bomb a distance of 7000 km. After several test failures, the R-7 successfully launched on August, 1957, sending a dummy payload to the Kamchatka Peninsula.

In 1957, during the International Geophysical Year, the concept of launching a satellite began to appear in the American press. The US government was not well disposed toward the idea of spending millions of dollars on this concept, and so it was effectively frozen for a period. However Korolyov's group followed the Western press, and they thought it possible to beat the US to the punch. He was finally able to win over support because of competition with the U.S. by suggesting that the USSR should try to be the first country to launch a satellite.

The actual development of Sputnik was performed in less than a month. This was a very simple design, consisting of little more than a polished metal sphere, a transmitter, thermal measuring instruments, and batteries. Korolyov personally managed the assembly, and the work was very hectic. Finally on 4 October 1957, launched on a rocket that had only successfully launched once, the satellite was placed in orbit.

The effect of this launch was electric, and produced many political ramifications for the future. Khrushchev was pleased with this success, and decided that it should be followed up by a new achievement in time for the 40th anniversary of the October Revolution. This was less than a month away, on 3 November. The result was Sputnik 2.

This new spacecraft would weigh six times the mass of the Sputnik 1, and would include as a payload the dog Laika. The entire vehicle was designed from scratch within four weeks, with no time for testing or quality checks. It was successfully launched on 3 November and the dog was placed in orbit. There was no mechanism designed in this vehicle to bring the dog back to Earth and so it died soon after succumbing to heat exhaustion.

This string of successes ran out with the launch of Sputnik 3. This instrument-laden spacecraft was sent into orbit on May 15th the following year. However the tape recorder that was to store the data failed after launch. As a result the discovery and mapping of the Van Allen radiation belts were left to the American's Explorer 4 in July. What the Sputnik 3 did do, however, was to leave little doubt with the American government about the Soviet's pending ICBM capability.

Korolyov now turned his attention to reaching the Moon. A modified version of the R-7 launch vehicle would be used, with a new upper stage. The engine for this final stage was the first designed to be fired in outer space. The first three probes sent to the Moon in 1958 failed. The Luna 1 mission in 1959 was intended to impact the surface, but missed by about 6000 km. Another probe failed and then the Luna 2 successfully impacted the surface, giving the Soviets another first. This was followed by an even greater success with Luna 3. It was launched only two years after Sputnik 1, and was the first spacecraft to photograph the far side of the Moon.

Korolyov's group was also working on ambitious programmes for missions to Mars and Venus, putting a man in orbit, launching communication, spy and weather satellites, and making a soft-landing on the Moon. A radio communication centre needed to be built in the Crimea to control the spacecraft.

Korolyov's planning for a manned mission had begun back in 1958, when design studies were made on the future Vostok spacecraft. It was to hold a single passenger in a space suit, and be fully automated. The capsule had an escape mechanism for problems prior to launch, and a soft-landing and ejection system during the recovery.

On 15 May 1960 an unmanned prototype performed 64 orbits of Earth, but failed to return. Four tests were then sent into orbit carrying dogs, of which the last two were fully successful. After gaining approval from the government, a modified version of the R-7 was used to launch Yuri Alexeevich Gagarin into orbit on 12 April 1961, the first person in space. He returned to Earth via a parachute after ejecting at an altitude of 7 km.

Following Vostok Korolyov planned to move forward with Soyuz craft that would be able to dock with other craft in orbit and exchange crews. However he was directed by Khruschev to cheaply produce more 'firsts' for the manned programme. Korolyov was reported to have resisted the idea, since he currently lacked a rocket of sufficient capability to lift a three-man capsule into space. However Khruschev was not interested in technical excuses and let it be known that if Korolyov couldn't do it, he would hand the work off to his rival Vladimir Chelomei.

To complete this task his group designed the Voschod, an incremental improvement on the Vostok. One of the difficulties in the design of the Voskhod was the need to land it via parachute. The three-person crew could not bail out and land by parachute, since the altitude would not be survivable. So the craft would need much larger parachutes in order to land safely. However some tests with the craft resulted in failures, causing the death of some test animals. This gave Korolyov pause, but the problem was solved through the use of new parachute material.

The resulting Voschod was a stripped-down vehicle from which any excess weight had been removed. Another modification was the addition of a backup retrofire engine, since the more powerful Voschod rocket used to launch the craft would send it to a higher orbit than the Vostok, thus eliminating the possibility of a natural decay of the orbit and reentry in case of primary retrorocket failure. This spacecraft made one unmanned test flight, then on 12 October 1964 a crew of three cosmonauts was launched into space and made sixteen orbits. This craft was designed to perform a soft landing, thus eliminating a need for the ejection system. The crew was also sent into orbit without space suits, another risky move.

With the Americans planning a space walk with their Gemini programme, the Soviets decided to trump them again by performing a space walk on the second Voschod launch. After rapidly adding an airlock, the Voschod 2 was launched on 18 March 1965, and Alexei Leonov performed the world's first space walk. The flight very nearly ended in disaster and plans for further Voschod missions were shelved. In the meantime the change of Soviet leadership with the fall of Kruschev meant that Korolyov was back in favour and given charge of beating the US to landing a man on the moon.

For the moon race, Korolyov's staff designed the immense N1 rocket. He also had in work the design for the Sojuz manned spacecraft (which went on to carry the first space tourists), as well as the Luna vehicles that would soft land on the Moon and unmanned missions to Mars and Venus. But, unexpectedly, he was to die before he could see his various plans brought to fruition.

Under a policy initiated by Stalin then continued by his successors, the identity of Korolyov was never revealed until his death. His obituary was published in Pravda on 16 January 1966, showing a photograph of Korolyov with all his medals. He was buried with state honours in the Kremlin wall. The town of Kalingrad (formerly Podlipki) is the home of RSC Energia, the largest space company in Russia. In 1996, Boris Yeltsin renamed the town to Korolyov. There are some astronomical features named after Korolyov, including Korolyov crater on the far side of the Moon and another crater on Mars. The asteroid 1855 Korolyov is also named for him.

| Sergey Pavlovich Korolyov Серге́й Па́влович Королёв Сергій Павлович Корольов | |

|---|---|

Sergey Korolyov in Red Army uniform (1938) | |

| Born | 12 January [O.S. 30 December 1906] 1907 Zhytomyr, Russian Empire (nowUkraine) |

| Died | 14 January 1966 (aged 59) Moscow, USSR |

| Cause of death | Tumor |

| Ethnicity | Ukrainian |

| Occupation | Soviet rocket engineer and designer Colonel (Red Army) |

| Spouse | Xenia Vincentini Nina Ivanovna Kotenkova |

Children Sergey Korolyov on Soviet Union 1969 Stamp10 kopeks | Natasha |

"The Chief Designer" Sergei Korolev (left) and "the Chief Theoretician" Mstislav Keldysh (right). In the centre: Igor Kurchatov, 1956

|

| Korolyov sitting in cockpit of glider "Koktebel." |

|

| Korolyov's tomb (left) in the Kremlin Wall Necropolis. |

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

R-5 Science Payload with Dog

R-5 Science Payload with Dog Korolev with Vladimir Yazdovsky

Korolev with Vladimir Yazdovsky The PS-2 Satellite

The PS-2 Satellite Transparent Model of Dog Cabin

Transparent Model of Dog Cabin Solar UV and X-ray Sensor

Solar UV and X-ray Sensor KS-5 Cosmic Ray Counter

KS-5 Cosmic Ray Counter Early Morning Launch of PS-2

Early Morning Launch of PS-2 Illustration of PS-2 in Orbit

Illustration of PS-2 in Orbit Laika With Implanted Biometric Sensors

Laika With Implanted Biometric Sensors Laika's Heart Rate During Flight

Laika's Heart Rate During Flight Data from Solar X-Ray Experiment

Data from Solar X-Ray Experiment Nov. 7 Cosmic-Ray Data

Nov. 7 Cosmic-Ray Data