Sputnik-2

| |

| Operator | Soviet Union |

|---|---|

| Major contractors | OKB-1 |

| Mission type | Earth Science |

| Satellite of | Earth |

| Orbits | ~2,000 |

| Launch date | November 3, 1957 at 02:30:00 UTC |

| Launch vehicle | R-7/SS-6 ICBM |

| Mission duration | 162 days |

| Orbital decay | April 14, 1958 |

| COSPAR ID | 1957-002A |

| Homepage | NASA NSSDC Master Catalog |

| Mass | 508.3 kg (1,120 lb.) |

| Orbital elements | |

| Semimajor axis | 7,314.2 km (4,545 miles) |

| Eccentricity | .098921 |

| Inclination | 65.33° |

| Apoapsis | 1,660 km (1,031 miles) |

| Periapsis | 212 km (132 miles) |

| Orbital period | 103.7 minutes |

| Instruments | |

|---|---|

| Dog Laika: | Biological data |

| Geiger counters : | Charged particles |

| Spectrophotometers: | Solar radiation (ultraviolet and x-ray emissions) and cosmic rays |

Following the excitement over the first artificial Earth satellite, Premier Khrushchev urged Korolev to launch a second satellite in time to celebrate the 40th anniversary of the Soviet revolution. Object-D was still months away from completion, but some experiments were ready to deploy immediately. PS-2 was assembled in less than a month, but was able to perform the first serious scientific experiments in orbit.

Korolev was interested in manned spaceflight at a very early point, and in 1949 he asked Vladimir Yazdovsky, an army physician, to head the biomedical research effort to study this problem. In 1955, Oleg Gazenko joined Yazdovsky's team and worked closely with him on problems of space biology and medicine. These experiments began with Korolev's R-1A missile, which tested the new concept of an ejectable warhead. Whole rockets, like the German V-2, sometimes broke up from aerodynamic stress as they approached their target, a problem that would get worse with larger and faster missiles. Yazdovsky launched the first dogs, named Dezik and Tsygan, on June 22 1951, using an R-1A sounding rocket and a sealed capsule with oxygen supply and soda-lime scrubbers to remove carbon dioxide. From 1954 to 1956, the R-1D and R-1E rockets carried pairs of dogs wearing pressure suits with plexiglass bubble helmets. The dogs were ejected from the rocket, one at 75-90 km altitude and the other at 35 km, to test different landing systems. From 1957 to 1960, the R-2A and R-5A went dogs to 200 and 480 km. For these experiments, Yazdovsky returned to the use of sealed compartments. In all, 29 launches with pairs of dogs took place Problems of interest included biometric sensors and telemetry, supplying the passenger with oxygen and food, studying the effects of weightlessness, and studying the effects of high acceleration that takes place during launch and reentry. These rockets also contained experiments for measuring primary cosmic rays, the far-ultraviolet spectrum of the Sun, micrometeorites and the composition and ionization of the outer atmosphere. Experiments housed on Sputnik-2 and Sputnik-3 were all tested on geophysical rockets.

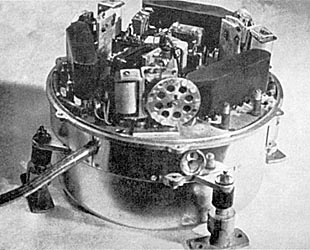

The PS-2 satellite consisted of three units mounted in a conical frame, with a total mass of 508.3 kg. At the top was an experiment to measure solar x-ray and far ultraviolet radiation. Below that was a spherical unit which was essentially the same as the original PS-1. Unlike PS-1, the 20 MHz signal was a more rapid pulsation, and the 40 MHz channel sent a continuous carrier. Below that was a cabin to carry an experimental dog. PS-2 remained attached to the rocket sustainer stage while in orbit. This permitted the R-7 (Tral) telemetry system to transmit science data. While the public was encouraged to listen for the 20 and 40 MHz signals, the scientific data would be sent on classified frequencies, 66 and 70 MHz. The sustainer stage also housed two Geiger counters. The aluminum dog cabin was adapted from a system used to carry dogs on the R-2A sounding rocket. It was 80 cm long and 64 cm in diameter. A ventilator fan at the top would turn on, if the temperature rose above 15° C. On either side of the dog, two large compartments contained plates of potassium superoxide. This chemical reacts with carbon dioxide and water vapor and emits oxygen (note small red circulating fans in the image above). A control system (above the left superoxide compartment) would stop regeneration if the pressure went above 765 mm Hg, to prevent the dog from being poisoned by oxygen. Food and water requirements were simultaneously met by a gelatinous nutrient made from water, agar agar, dried-bread powder, powdered meat and beef tallow. This was delivered by a cartridge belt arrangement that doled out portions for the dog to eat at regular intervals. A 3 liter supply was meant to last seven days, which was also how long oxygen regeneration would last. Urine and feces were collected by a tight fitting rubber cup, and sent to a sanitation reservoir filled with activated charcoal and dried moss.

The sun emits far ultraviolet and x-ray radiation from the high temperature plasma in its corona. Since these wavelengths did not penetrate the atmosphere, American and Soviet scientists had studied them with sounding rockets, but there was no long term study to connect this radiation with changes in the ionosphere. Prof. Sergey Mendalshtam, at the Lebedev Institute of Physics, designed a detector that was ready in time for the PS-2 mission. It consisted of three photomultiplier tubes, aimed at 120° intervals. A filter wheel revolved in steps to select different wavelengths: copper (0.14-0.3 nm), beryllium (0.5-1.0 nm), aluminum (0.8-2.1 nm), polystyrene(4.4-10.0 nm) lithium fluoride and calcium fluoride for the hydrogen Lyman-α wavelength (121.5 nm) and quartz (great than 150 nm). At Moscow State University, cosmic-ray expert Sergey Vernov and his colleagues were preparing a Geiger-counter unit for Object-D. The KS-5 cosmic counter (kosmicheskii schetchik) consisted of an SI-17 gas discharge tube, commonly used in high-altitude balloon studies of cosmic rays. Given a power budget of only 2 watts, they could not use vacuum tube for the electronics. They considered neon-lamp logic and cold-cathode thyratrons, but eventually decided to use the new technology of solid state transistors and diodes. They were surprised by the launch of Sputnik-1, and when Vernov heard about PS-2, he rushed to meet with Korolev. Arguing the importance of cosmic-ray measurements for manned spaceflight, he convinced Korolev to let them install their device on the upcoming mission. They were given enough space on the sustainer stage for two KS-5 units, and a Tral telemetry channel was allocated. But there was no additional electrical power available for them. With only three weeks until launch, the KS-5 was quickly modified to contain its own battery power supply.

The second artificial Earth satellite was launched on November 3, 1957, at 2:30:42 GMT. It reached an orbit with a perigee of 225 km, apogee of 1671 km and a period of 103.75 minutes. The plane of the orbit was inclined 65.33°. A strong spring ejected the conical fairing, and two oxygen gas jets backed the satellite and sustainer stage away, to avoid collision with the fairing. Two symmetrically placed jets were used, instead of one as on Sputnik-1, to avoid imparting extra rotation to the satellite. Once in orbit, the Tral system changed from reporting rocket telemetry to a program of switching between four sets of mission data: solar x-ray data, cosmic-ray counts, biometric data on the experimental dog, and temperature readings from 12 points on the spacecraft. The satellite completed 2570 orbits. It was observed reentering the atmosphere over the West Indies on April 14, 1958.

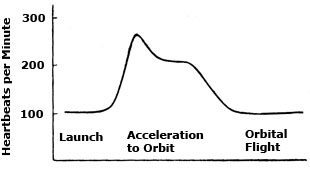

Sputnik-2's passenger was Laika, a small dog of mixed breed (possibly siberian husky and terrier) collected off the streets of Moscow. In preparation for the flight, Laika was trained to sit in the cabin and get used to the noises and acceleration of launch and to the harness and waste-collection apparatus. Four biometric readings were radioed to Earth. Silver EKG electrodes were implanted in the chest to measure the heart rate, and a piezoelectric blood-pressure sleeve was surgically placed around the carotid artery in the neck. These were kept carefully bandaged and cleaned with alcohol to avoid infection where wires emerged through the skin. Respiration rate was measured by strain gauges in a belt around her chest. The dog was chained in place, with limited freedom to lie down or stand, and motion sensors reported activity. Heart-rate telemetry indicated that Laika was stressed by the launch and possibly surprised for a time by the transition to weightlessness. Respiration rate increased, reaching 4 times normal during the period of greatest acceleration, when pressure made it physically difficult to breath. 5-10 minutes after the achievement of orbit, the dog calmed and her readings and activity returned to normal. Yazdovsky was concerned from the start about the problem of heat, both from the Sun and from the dog's body. The decision to keep the satellite attached to the sustainer stage may have exacerbated the problem. During the flight, the cabin became steadily warmer. Sometime after the 4th orbit (5 to 7 hours) the biometric telemetry system failed. Although Laika's exact fate is unknown, ground simulations suggested that she died from overheating soon after the 3rd or 4th orbit. Official news reports described the results from the early hours of the experiment. Subsequently, no details were announced except to suggest that Laika, who had become an instant celebrity, was fine. When the radio transmitter stopped on November 10, officials began to acknowledge that Laika would die. An Italian communist paper reported (and later retracted the story) that Laika was euthanized by poison, but there is no evidence that such a thing was ever planned or implemented in the life support system.

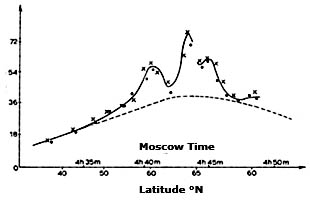

Data from Mandelshtam's solar x-ray experiment was disappointing. While changes could be seen from the filter wheel steps, for the most part the sensitive photomultiplier tubes appeared to be jammed by intense radiation that had no connection with the direction of the Sun. His team did not publish the results, and in retrospect, Mandelshtam realized that they had seen the effects of proximity to the Earth's radiation belt. Vernov's team had better luck with the KS-5, and they received data from November 3rd to the 9th. Of particular interest was an event on November 7, when an elevated level of radiation was seen at about 60° latitude. We know now that this is where the fluctuating outer radiation belt approaches the Earth most closely. They had no way at the time of realizing the significance of this anomaly. The signal from Sputnik-2 could only be received over the territory of the USSR. The apogee of the orbit occurred high over the south pole, where it would have penetrated well into the radiation belt, but that data was never seen. Because the mission data was being sent on a classified channel, Vernov could not ask for help from his international colleagues, and he would be mindful of that problem on the next satellite mission.  In 1957, Laika became the first animal launched into orbit, paving the way forhuman spaceflight. This photograph shows her in a flight harness. Romanian stamp from 1959 with dog Laika |

R-5 Science Payload with Dog

R-5 Science Payload with Dog Korolev with Vladimir Yazdovsky

Korolev with Vladimir Yazdovsky The PS-2 Satellite

The PS-2 Satellite Transparent Model of Dog Cabin

Transparent Model of Dog Cabin Solar UV and X-ray Sensor

Solar UV and X-ray Sensor KS-5 Cosmic Ray Counter

KS-5 Cosmic Ray Counter Early Morning Launch of PS-2

Early Morning Launch of PS-2 Illustration of PS-2 in Orbit

Illustration of PS-2 in Orbit Laika With Implanted Biometric Sensors

Laika With Implanted Biometric Sensors Laika's Heart Rate During Flight

Laika's Heart Rate During Flight Data from Solar X-Ray Experiment

Data from Solar X-Ray Experiment Nov. 7 Cosmic-Ray Data

Nov. 7 Cosmic-Ray Data

No comments:

Post a Comment